I.

This blog post grows out of an exercise on temporality that my Digital Humanities class undertook a few weeks ago. For the exercise, I chose to consider a webpage called Classical Art Memes, with emphasis on the way it combines high art, low/vulgar interventions, and the meme culture of remix and remediation. I also chose to examine notions of cultural memory, print culture v. the new media universe with specific regard to the notion of fixity as defined by Elizabeth Eisenstein, and the evolving nature of language.

In the fields of book history and print culture, Elizabeth Eisenstein is known as one of the greatest historians of the book within the field. Her writing about the print revolution has as one of its central claims that one of the effects print and printing had was something she termed “fixity,” by which she means the way in which knowledge grew increasingly “fixed” or pinned down as they were printed in increasingly standard forms, and standard versions of books were reproduced and disseminated from library to library across the world. Eisenstein claims that we only really have a western tradition of knowledge because it is based on the print revolution which created stable, fixed forms of knowledge, and perhaps we can extrapolate that to include cultural memory as well, if we include things like the literary canon.

However, we now find ourselves in a new media universe in which fixity seems a distant dream. There are attempts made to “fix” the web and pin it down as it is, through something like the internet web archive, but even then, this is not the fixity we want, because it lacks the authority and the reliability of the Official Archive, or Repository, Library, Holding, etc. The web is in a state of constant flux, almost like a living thing or a tidal ocean, and the web archive can only give us records, like snapshots, of ways that it has been – what is missing, then, is the stability of future expectations. While chapter 6 of Bleak House will be, in essence, the same in twenty or forty or two hundred years, and you could go to a library in the future and read it because it is “fixed,” we have no way of anticipating the web that way. This was clear even in McLuhan’s day; the new media age is instant and simultaneous – the light switch is on, and this is how the global village exists. Everything that is happening happens at the same time. It is no longer sequential, in the plodding, one-foot-in-front-of-the-next way of print. Without this fixity, though, we are now scrambling both conceptually and grammatically to find new ways to think about what the experience of historicity and of time might be in the new media age.

I posit that the meme is to the new media universe what the book is to print culture. (Loosely.) It is both medium and message, it represents cultural memory better than any other media format I can think of, and it functions as simultaneous iteration and emulation of both history and memory. Alan Liu has said that at this very moment, we find ourselves on the

“seam of a tremendous destabilization of notions of historicity and of temporality, and just like we are with the notion of reading where we are inventing all these words, distant, close, surface, etc, to try to stabilize once more what we mean by reading, the experience of historicity and temporality are so unstable that we are reaching for new concepts and words.”

We see this reflected in so many different aspects of our lives and our culture, and even our language, with the explosion of post-digital retronyms like “analog clock” when pre-digital clocks were just called “clocks,” or “film camera” has to specify that its functionality materially differs from the digital. It’s as though we are retro-fitting a vocabulary onto media archaeology.

I do not argue that memes offer similar stability or that they are equivalent to books in terms of generating fixity in print culture. Instead I suggest that they can be read metonymically for the larger, more generative, and more flexible fixity that finds purchase in the new media universe.

II.

The exercise:

Classical art is a good place to begin contemplating an exercise on temporality. The very term “classical art” refers, in its purest and most correct sense (that is to say, correct to art historians), to the art of ancient Greece and Rome.

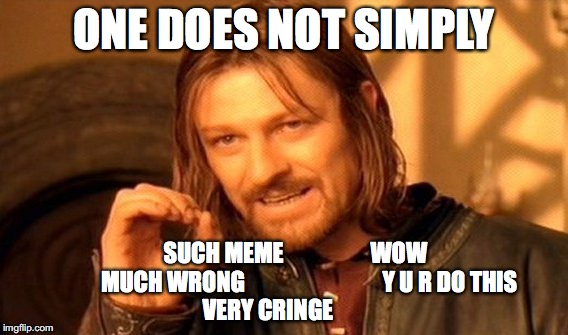

If we can consider time and age as a form as aesthetic remediation, then classical art is endowed with one of the most enduring legacies of cultural currency. That said, the website Classical Art Memes does not limit itself to art from the classical period and world – the Waterhouse portrait of Ophelia used as the example here is quintessentially Pre-Raphaelite, and therefore about 19 centuries too late to qualify as properly classical. This implies something about how the content creators are thinking about the “high” art (read: Western European art historical tradition, usually oil paintings) that they use as a vehicle for their memes; the veneer of elegant, polished, high art is used to lend contrast to the silly colloquial text content that make up the rest of the meme. Because the content creators (mis)use “classical art” as a synonym for high art, they signal to us that we are meant to understand all high art as a meme-like backdrop for a given kind of meme. In the same way anytime we see Sean Bean in his LOTR Boromir costume, and know to expect a “One does not simply” meme, all “high” art becomes a meme for itself, visually, within the larger frame of the meme it makes up.

Let us consider, for a moment, the anatomy of the meme media format. It consists of an image as a backdrop, and text over it, and the interplay between these two create a new kind of message. They are almost always meant to be funny, and are a pastiche of art, text, single-frame cartoon, illustration, and pithy quote. In terms of language – always an important thing to consider when thinking about temporality and media evolution – they have also developed a grammar and a syntax all of their own. For instance, there have been analyses done by linguists on the Doge memes, proving that there are correct and incorrect ways to write them.

In the Doge meme’s linguistic universe, “such meme” is correct, but “such mediality” would not be since it would technically be possible to use it correctly in a sentence in English. In the same way, “much cute,” is more correct than “much cuteness,” and then there’s the fact that the word “wow” can go anywhere and supersedes the otherwise fairly rigorously set internal logic of the Doge meme syntax. The utter irrationality of that fact makes it, interestingly enough, quite like real languages – every language I can think of has some sort of inexplicable rule that must be respected: English certainly, French certainly, Italian has nouns that change gender when they are plural, and no one knows why other than to say it’s a holdover from Latin, ditto Spanish. Mandarin has no verb tenses, which always hurt my brain, and Arabic’s written and spoken languages and their respective, distinct rules are so distant from each other that to speak the written version out loud would be like me speaking to you in Chaucer’s English.

Much in the same way language evolves in unpredictable and sometimes nonsensical ways, memes are evolving to have a grammar and a syntax all their own. If we can consider memes this way, then we can also begin to consider meme-indexing websites like Know Your Meme (aka the Internet Meme Database) as proto-dictionaries and style guides. There is a logic by which the memes are sorted, namely into categories like: confirmed, researching, popular, submissions, and deadpool, and which can be cross-tagged with the following: events, memes, people, sites, and subcultures. There is no criteria listed on the website to explain how a meme moves from “submission” to “popular” and then “confirmed” (if that is even indeed the order in which things progress) and, at the time of writing, the website more closely resembles LOLcats than OWL Purdue, but ultimately what matters here is that there is even an attempt to create an Internet Meme Database.

This is suggestive of two points that dovetail with Eisenstein’s concept of fixity: 1. That fixity in the new media/internet universe is significantly more difficult to achieve than it is (or was) in print culture; and 2. That despite this increased complexity, the human impulse towards fixity persists, and this is why there are “correct” and “incorrect” internal logics and grammars operating within meme types like the Doge memes, and the classic “One does not simply” memes. For example, below I’m including a “wrong” meme in which I’ve “broken” the rules of both memes’ internal logics:

Much as in the case of grammatical errors, we recognize them and we know that they are erroneous, but it can be hard sometimes to pinpoint exactly why. Part of what gives memes cultural power, then, might be less about their internal logics and more to do with their easily internalized logics. This internalization is the new media universe’s answer to Eisenstein’s fixity. Rather than depending on the texts’ multitudinous existence to assure their fixity, as in print culture, then, we can perhaps begin to understand memes’ fixity through pop culture’s easy, even eager internalization of their form and content, their medium and their message. And so begins the formulation of a grammar, or at least a structured way of thinking about memes and their cultural function.

In the case of the Classical Art Memes, their language’s internal logic coheres around rude or lewd statements, often full of innuendo (or sometimes more explicit content), and they are rife with the abbreviations that web language has given rise to, like “OMFG” as well as uniquely lower-case lettering (see the above Ophelia frame). In this way, the Classical Art Memes format appropriates the elevated tone that the fine arts and high art sets, a tone that it acquires by virtue of being old art as much as by being good art, and radically transforms it.

These memes make a mockery of the art through their intermediality, and in that way also make fun of the entire concept of high/fine/elevated art. Their refusal to adhere to art historical terms, that is to say to only use examples of classical art from the Greco-Roman world, then, is not evidence of ignorance on the subject of classical art, but rather a way of understanding that high/fine art demands to be paid a certain kind of attention, and a way of answering, to put it the best way I can to make this point:

Through this denial or high culture’s own insistence to command a certain modicum of respect, these memes demonstrate a shift in modes of cultural memory. And if we understand cultural memory as a mutable parcel of memory, history, and time that is constantly in a process of being transmitted, perhaps even virally, as we say, then that is effectively also the definition of a meme. This speaks to the original definition of the word “meme,” which of course shares a common root in Greek with the words “memory,” “mimesis,” and “mnemonic.” Memes, in the original sense, can be defined as repeated ideas that are culturally transmitted, often through repetitions and imitations. In this way, they act as an almost living memory that gets passed around a culture, and there is none of the care about authenticity that “fixity” demands, making them flexible fixities operating at a different order of magnitude. At a time when cultural memory, as it has been institutionalized in its iterations as the humanities and, more specifically, the literary canon, I will end this post with a provocation: Could it be that in the future the humanities will be not a mode of cultural memory, but of cultural memes?