Here’s my takeaway from Wuthering Heights:

Nelly: Catherine just died, Heathcliff

Heathcliff: Yeah but did she mention me?

Fuckboy. Fuckboys everywhere.

Full disclosure: I think there are a lot of problems with the way this book gets taught these days. I find it utterly staggering that this novel is upheld as the quintessence of romance by teenaged girls all over. I find it worrisome that, in this age of increasing awareness about rape culture, it’s still considered a good choice for high school curricula all over. It is full of assaults, child/verbal/emotional/physical abuse, vicious manipulations, revenge, kidnapping, forced marriage, obsessive behavior, and just too much else to name.

Tl;dr: This book is a goddamn nightmare, and should be used as a manual for how to look for red flags in all kinds of human interactions, rather than taught in high schools as one of the greatest love stories ever told.

I think one of the most important things that gets shoved aside when we are thinking about this book is that the Gothic, as a genre, is often parodic. Even when it doesn’t mean to, it laughs at itself – blending horror and romance simply lends itself to this too well not to. This is not to say that these are comedic, or to fall back on the old high school standby of trying to sort out the author’s intention. I’m just suggesting that if you read a Gothic novel “straight” you’re going to miss out on a lot of what makes them wonderful, interesting, and worth reading.

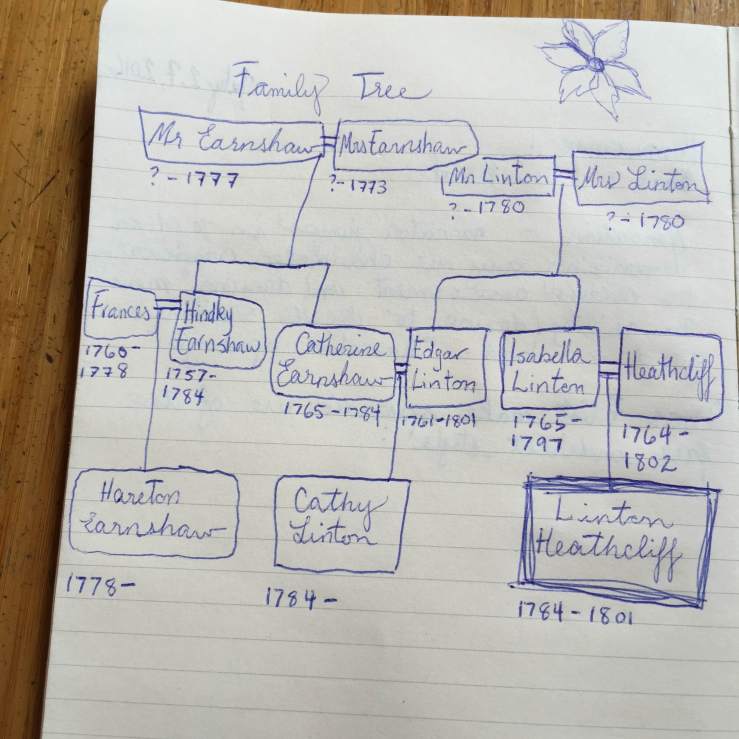

For example, here’s the family tree from Wuthering Heights:

Now, I would suggest that readers derive some small amusement from the increasing confusion that proliferates as the novel progresses and all the new characters have the same names as the previous generation. This is Brontë gently but cleverly teasing the Gothic genre and its rabid fans for the convolutions they embrace so fully. There’s clearly a sense of humor at work here, because otherwise it would simply be silly and ridiculous. Now, the Brontës are many things, but I refuse to believe that they were silly lady novelists (more on this when we get to Charlotte and Jane Eyre), not when there is such a mastery of the human condition at its worst. Wuthering Heights paints bitterness, baseless hatred, soul-eroding jealousy, regret, and vicious self-loathing better than any novel I know. Even the landscape, described as “a perfect misanthropist’s heaven,” takes on an almost human animus, and Wuthering Heights, the house from which the novel takes its name, acts as a focal point for the story’s swirling miasma of despair. The love in this novel, then, should be regarded with suspicion, with the same guarded awareness with which Pandora saw hope at the bottom of the box of evils. Is it meant as a palliative for all the bad in the world? Or is it at the bottom because it is the worst of all? Love is not a beneficent force in Wuthering Heights; it is actually a vehicle that drives a lot of evil doings forward. In this respect, it becomes a really interesting place to think about what it means for this to be a Gothic novel, in terms of how it performs the conventions of romance and horror particularly.